Why

March? Seriously, what is the

point? Do the public listen to what

people are shouting/banner waving about?

Does the Press care? It seems not

last Saturday when up to 50,000 people marched through London protesting about

the austerity cuts. JENGbA families

wanted to march that day so I called and was told we could, of course, join

in.

We were at

the back of the march, as a campaign against austerity I suppose we did not

naturally seem to fit in with our anger at people being wrongfully imprisoned

for crimes they did not commit and serving mandatory Life sentences. That was ok - JENGbA families are used to our

concerns being ignored (though not for much longer!).

So back to

my question: Why March? The JENGbA

families seem to have got the bug! We

did one last month which was filmed for a BBC documentary that will be shown

the night after Jimmy McGovern's film 'Common' and also by a group of students

using the subject of Joint Enterprise for their final film for their MA in TV

from City University. To be fair having

media attention did give our march an added buzz but that is not the reason I

believe JENGbA families want to walk in the streets shouting "Joint

Enterprise is a court full of lies!" and "No Justice, No Peace".

The JENGbA families in the North of

England also held a rally in Manchester Piccadilly Gardens and via twitter and

calls we realised they too felt empowered by educating people on the streets

who had not heard of JE before and how it is being abused.

Families

want to march because they feel helpless, angry, frustrated and depressed about

what can be done when you have an innocent loved one in prison and are being

totally ignored by the British justice system.

They proudly hold aloft their banners displaying pictures of their

family members before they became prisoners of the State. Kelly and Maureen's Smith dad Kevin and

grandson travelled down from Liverpool for it and a mum had travelled back from

Saudi Arabia to be there. Solidarity is

a very powerful emotion and since most of our families have a loved one in

prison who is deemed a 'murderer' just to meet other families in a similar

situation is an invaluable support network.

On the

morning of the People's Assembly March, Jan Cunliffe called me to say that our

friend and supporter Gerry Conlon had died and that she had spoken to Paddy

Hill. Another reason to march and

empower families as that is exactly what Gerry and Paddy have been doing since

they were released from prison. Gerry

showed through his own activism, even through the most difficult of personal

times, that we must never forget how devastating an injustice is a wrongful

conviction and never stop fighting for the oppressed and vulnerable people in

prison.

|

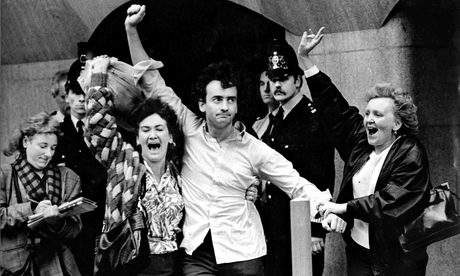

| JENGbA at People's Assembly March |

We have

always described JENGbA as a family and as we grow bigger and stronger so does

our family. We are seeing friendships

being made of people who would have never met except for this campaign. More families and supporters came to the

People's Assembly march and they want to do another JENGbA march after Jimmy

McGovern's film is screened on July 6th.

They have certainly got the marching bug! We know that to be able to DO something is one

of the ways families do not sink into depression and despair. And to be able to

feel like you are DOING something for a whole lot of people and not just your

own, is a whole different feeling of empowerment. That will only grow as our numbers do and

then we will no longer be ignored.

Finally the

reason we marched with / bandwagoned the People's Assembly against Austerity is

because it costs on average £50,000 a year to keep each innocent man, woman and

child locked up. JENGbA is currently

supporting 450 serving prisoners convicted using joint enterprise who have

contacted us. That is at least £22.5 million

annually spent on denying justice to the Joint Enterprise prisoners we know

about and there could be many more whose lives are blighted by unfair

convictions.

An

increasingly sinister aspect to this growing burden on the taxpayers is how

much of this money goes to fatten the directors’ salaries and profits of the

UK’s private prison industry. There is

something seriously wrong when the UK has more Lifers than the rest of Europe

combined and has the highest percentage of prisoners in private jails in the

world (yes, even higher than the USA!).

If Slavery

is about the commercial exploitation of men, women and children by unjustly

denying them freedom and human rights, what does that make G4S, Serco and

Sodexo? And what does that make the directors

and shareholders of these companies…or the Ministry of Justice for buying their

services?

Gloria

Morrison

Campaign

Co-ordinator JENGbA